The mention of 19th century authors in the manuscript of Countess of Elise de Perthuis was limited to a brief mention of Alphonse de Lamartine. Knowing that travels to the orient at the time were extensive, the mention of her contemporaries was rather.

Lamartine & Lady Stanhope

“the beautiful plane trees” mentioned by Alphonse Lamartine.

On October 3rd 1853 the Countess refers to “the beautiful plane trees” mentioned by Alphonse Lamartine. Below is her journal entry on this day.

“Nous débarquons à Rhodes. Les remparts et la belle tour. La rue des Chevaliers et ses écussons. Nous reconnaissons sur une maison les armes des Perthuis. L’église Saint-Jean devenue mosquée le palais des grands maîtres n’est plus qu’une ruine. M. Bruce consul de France nous fait faire une promenade à la vallée des zimbole (violettes). Les beaux platanes chantés par Lamartine. Repos au café turc, nous y rencontrons le bourreau, les musulmans l’honorent. L’Africa se remet en route pendant le dîner du bord.”

The Countess was most probably referencing the Lamartine’s mention of the plane trees in his poem mostly sung by children, Le moulin au printemps,

….

Le bras d’un platane

Et le lierre épais

Couvrent la cabane

D’une ombre de paix.

…

Words of the Chancellor Mr. Jorelle, a close friend of Lady Hesther Stanhope

He denies what Lamartine says about his encounter with this lady

“…il a beaucoup connu Lady Stanhope et dément ce que M. de Lamartine raconte de son entrevue avec cette dame. La vérité est qu’elle a refusé de recevoir le poète et lui a seulement fait servir le café dans son kiosque.’’

The least that can be said is that Lamartine’s description of his encounter with Lady Stanhope might be slightly exaggerated based on what Mr. Jorelle told the Countess.

Lamartine goes on and on about Lady Stanhope warmly welcome. He says that she expresses a sense of kinship in their shared appreciation for God, nature, and solitude. She claims to possess the long-lost science of astrology and offers to unveil Lamartine’s destiny. However, he respectfully declines, affirming his belief in God, freedom, and virtue over the pursuit of knowledge about the future. Lady Stanhope argues for the imminent arrival of a new Messiah, distinct from Jesus Christ, and engages in a discussion about her eclectic religious beliefs. Despite their differences, Lamartine finds her captivating and acknowledges her significant influence among the Arab populations.

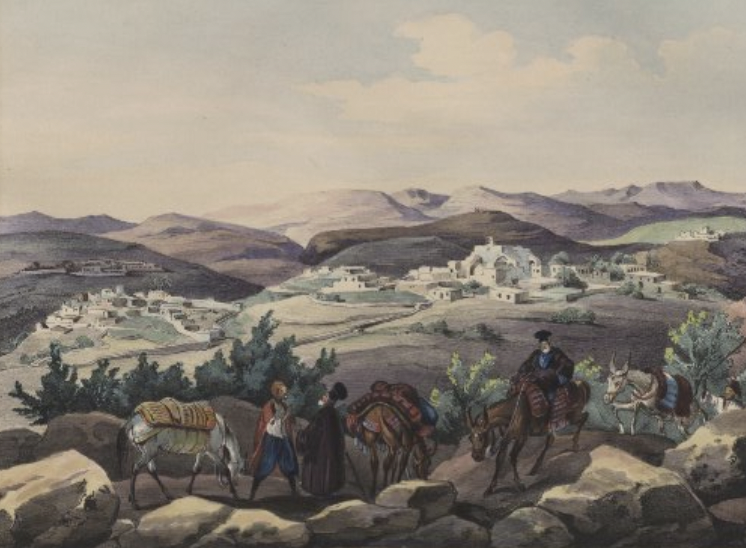

Reflecting on her life, Lady Stanhope expresses confidence in her destiny, despite facing numerous challenges and betrayals. Lamartine also observes and comments on Lady Stanhope’s attire, demeanor, and surroundings, noting her elaborate Eastern attire, the act of smoking a long oriental pipe, and her residence in a unique compound reminiscent of mountain monasteries. He reflects on her mystical aura and the impact she has on the people of the region, highlighting her visionary aspirations and potential future role in Arab politics, which underscore her ambition and influence in the Middle East.

The passage continues revealing more into Lady Stanhope’s character, her mystical beliefs, and her influence on Lamartine, as well as their philosophical exchange on societal issues and spirituality. She invites Lamartine to her private garden, which she describes as a sanctuary for herself and her trusted companions. He was enchanted by the beauty of the Turkish garden, which he describes as one of the most beautiful gardens he’s seen in the orient. It features lush greenery, intricate arabesque designs, grape-laden trellises, marble fountains, and fruit trees from various regions. Lady Stanhope then shows Lamartine two magnificent Arabian mares, one bay and one white, both of which are treated with great reverence and never ridden by anyone. She suggests that the bay mare fulfills a prophecy regarding the Messiah, as it appears “born saddled” due to a natural cavity on its back resembling a saddle. She also hints that the white mare has a mysterious and important destiny as well, potentially related to her own future role in the reconquered Jerusalem alongside the Messiah.

Despite their differences in social and political beliefs, Lady Stanhope and Lamartine engage in a philosophical discussion about aristocracy, democracy, and human nature. Lady Stanhope reveals her disillusionment with politics and her focus on God and virtue.

Lamartine expresses his belief in the equality and potential moral perfection of all human beings, regardless of social status, and finds common ground with Lady Stanhope in their shared emphasis on God and virtue he says:

“Milady, lui dis-je. Je ne suis ni aristocrate ni démocrate ; j’ai assez vécu pour voir les deux revers de la médaille de l’humanité, et pour les trouver aussi creux l’un que l’autre. Je ne suis ni aristocrate ni démocrate : je suis homme, et partisan exclusif de ce qui peut améliorer et perfectionner l’homme tout entier, qu’il soit né au sommet ou au pied de l’échelle sociale ! Je ne suis ni pour le peuple ni pour les grands, mais pour l’humanité tout entière ; et je ne crois ni aux institutions aristocratiques ni aux institutions démocratiques la vertu exclusive de perfectionner l’humanité ; cette vertu n’est que dans une morale divine, fruit d’une religion parfaite : la civilisation des peuples, c’est leur foi !”

“Cela est vrai, répondit-elle ; mais cependant je suis aristocrate malgré moi ; et vous conviendrez, … que s’il y a des vices dans l’aristocratie, au moins il y a de hautes vertus à côté pour les racheter et les compenser ; tandis que dans la démocratie je vois bien les vices, et les vices les plus bas et les plus envieux, mais je cherche en vain les hautes vertus…”

The evening unfolded with Lady Esther engaging in spontaneous and open discussion on various topics that naturally arise in conversation. Lamartine sensed that her sharp intellect comprehended every aspect thoroughly, like a well-tuned instrument producing harmonious and resonant tones, except for the metaphysical aspect. It seemed that prolonged solitude and intense contemplation had either distorted or elevated this aspect beyond the grasp of mortal understanding. Lamartine mentions in the end of his chapter that they farewell with genuine regret on his side and courteous reluctance on Lady Stanhope’s:

“Point d’adieu, me dit-elle : nous nous reverrons souvent dans ce voyage, et plus souvent encore dans d’autres voyages que vous ne projetez pas même encore. Allez vous reposer, et souvenez-vous que vous laissez une amie dans les solitudes du Liban. » Elle me tendit la main ; je portai la mienne sur mon cœur, à la manière des Arabes, et nous sortîmes.”